The Mind of a Player

How to use motivational models in gamification

When you can’t see the motivation for the models

The study of human motivation provides dozens of competing models, all respected, all explaining motivation differently. Gamification is finding out what motivates people to play games, and using that to motivate them to do other things, so models of motivation are indispensable. But which one to use?

It’s crucial to move beyond questions of which one is ‘right’. Each model has different assumptions, often trying to explain a different aspect of ‘motivation’. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs focuses on which human needs take priority when they compete. Herzberg’s Two-Factor theory tackles what motivates and demotivates at work. Some focus on types of people. Others have more to say about actions and activities.

Choosing a framework

But you don’t need to know which is ‘right’ in some abstract sense; you just need to know which is right for you. And this depends what you’re using the model for. Often, rather than creating peer-reviewed science, you’re seeking inspiration for practical ideas about what might work in a gamified experience. What you implement will be partly determined by the setting, and will be prototyped and tested.

Motivational models, then, are explanations that work as well as the solutions they inspire. You shouldn’t be looking for the one true model; you should look to which ones inspire the most useful thinking, by explaining the decisions and actions people take when they play games.

I find five particularly useful, mostly ones created specifically for gamification and game-based design. Each has strengths and weaknesses, and each can be more useful in some places than others.

Lazarro’s Four Keys to Fun

This framework was based on research directly into why people play games. Nicole Lazarro categorised people’s emotions and reasons for playing into four types of fun:

- Hard fun, from overcoming obstacles and achieving challenging goals

- Easy fun, from playful curiosity and creativity, with little direction or pressure

- People fun, from human interaction and creating and enjoying social bonds

- Serious fun, from finding real meaning in play, and changing the world and the self

This division aids focus. Which kind of play do you want your users or players to engage in more of? Which is most present or likely at the moment? What’s missing? How can you focus on the kind you want?

Marczewski’s Hexad

The Hexad is a model that focuses on player types, but links each to a drive. It was developed from Richard Bartle’s Player Types model which looked specifically at Massive Multiplayer Online RPGs, but it also has similarities to Self-Determination Theory, a classic Psychology model. I find it useful as it covers much of Self-Determination Theory’s focus on internally-driven motivators while also incorporating externally-driven ones.

- Socialisers are driven by Relatedness; they want to interact and create social connections

- Free Spirits are driven by Autonomy; they want to forge their own path and flex their own creativity

- Achievers are driven by Mastery; they want to learn, grow and overcome challenges

- Philanthropists are driven by Meaning; they want to give to others altruistically and make the world better for all

- Players are driven by Reward; they want to get what they can from the system

- Disruptors are driven by Change; they want to disrupt the system and shake things up

You don’t need to see people as one or the other of these for this to be a useful framework. Its broad focus can be a great jumping-off point for new ideas to suit a range of people.

Fogg’s Behavioural Model

Simple yet powerful, Fogg’s model can be summarised as B=MAP. Or, behaviour equals motivation, ability and a prompt.

- Motivation is simply how much a person wants to do an action, all other factors aside

- Ability is how easy it is for them to do that action, in a given moment

- Prompt is whether they have a prompt or trigger in that moment

So, getting people to take actions hinges on finding a moment where they want to do it and can do it easily, and making sure a prompt or trigger is provided at that moment.

It’s a very different approach to the first two. It doesn’t give as much wide-ranging inspiration about the kinds of things that might motivate, but it does help apply potential motivators in a given moment, to turn motivation into action. Or to figure out why a certain nudge isn’t working.

Flow Theory

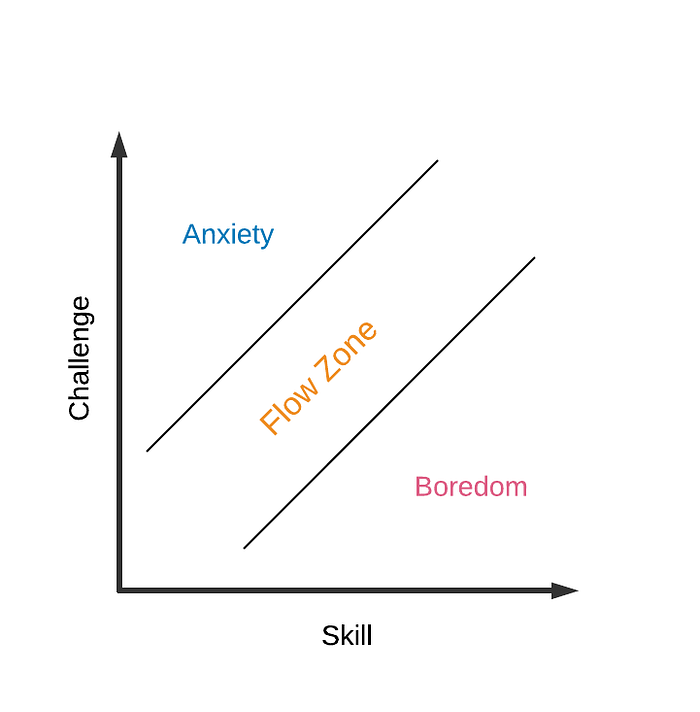

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s Flow Theory looks similar to Fogg’s Behavioural Model. But whereas Fogg focuses on prompts and making things as easy as possible in a moment before providing a prompt, Flow says that two things are key:

- The level of challenge

- The level of skill

It stresses the need to maximise and balance these two factors. Too much challenge without skill brings anxiety; skill without challenge brings boredom. The perfect balance of challenge and skill creates a highly-motivating sense of flow, or being ‘in the zone’.

This model can help you balance these two things, ideally in an ascending spiral — as ability increases, the level of challenge rises to meet it.

Octalysis

The Octalysis framework, developed by Yu-Kai Chou, suggests eight core drives which are present (or not) in an experience, and which good experiences will often include and balance:

- Epic meaning and calling — a sense that the player’s actions further a cause bigger than themselves, or a calling that is personal to them

- Development and accomplishment — making progress, developing skills and overcoming challenges, often shown by markers of progress

- Empowerment of creativity and feedback — having a chance to try different options and combinations, and see the results

- Ownership and possession — the sense that you own something, and want to increase its value or have it exactly the way you want it

- Social influence and relatedness — connecting to others and being motivated by them, whether via friendship, competition or acceptance

- Scarcity and impatience — the sense that something is desirable and valuable because it’s rare or difficult to get

- Unpredictability and curiosity — an element of surprise or mystery, leading you to want to find out more

- Loss and avoidance — motivation via the threat of losing something of value to you, or avoiding something unpleasant

This framework covers a lot of ground and has a lot of ‘hooks’ that can spark ideas, so it’s especially strong for analysing the strengths and weaknesses of an experience, and for brainstorming improvements.

Using them together

Some models map across to each other well. For instance, the Hexad’s ‘autonomy’ can be situated within Octalysis’ ‘empowerment of creativity and feedback’. But the focus is different, and the ideas it tends to prompt are different. Used as a space to think into, or a set of triggers, each framework will lead you in different directions.

To borrow an idea from the game designer Jesse Schell, each model can be thought of as a ‘lens’ through which to examine human behaviour in relation to games and gamification, and to prompt inspiration and progress. The more lenses, the more perspectives. The more perspectives, the more ideas you can test to find out which ones work for you.